Una familia de inmigrantes judíos en una comida en su nuevo hogar ecuatoriano en la década de 1940. (Cortesía Eva Zelig)/A family of Jewish immigrants at a meal in their new Ecuadorian home in the 1940s. (Courtesy Eva Zelig)

_______________________________________

Ecuador como refugio judío

Si bien muchos países hicieron menos de lo que podían cuando los judíos buscaron refugio del Holocausto, la pequeña nación sudamericana de Ecuador tuvo un impacto enorme. La antigua colonia española, que lleva el nombre del ecuador, se convirtió en un refugio improbable para entre 3.200 y 4.000 judíos entre 1933 y 1945. Pocos de estos refugiados sabían español al llegar, y muchos no lograban localizar su nuevo hogar en el mapa. Sin embargo, algunos emigrados lograron éxito en diversos campos, desde la ciencia hasta la medicina y las artes, ayudando a Ecuador a modernizarse en el camino. La creciente amenaza de Hitler y Mussolini estimuló la inmigración judía a Ecuador, apoyada por la pequeña comunidad judía local. El presidente José María Velasco Ibarra promovió el país como un destino para científicos y técnicos judíos alemanes repentinamente desempleados debido al antisemitismo nazi.

__________________________________________

El autor y académico radicado en Ecuador Daniel Kersffeld publicó un libro en español sobre esta historia poco conocida, “La migración judía en Ecuador: Ciencia, cultura y exilio 1933-1945”. “Inmigración judía en Ecuador: ciencia, cultura y exilio 1933-1945”. El autor examinó 100 relatos biográficos al escribir el libro. En una entrevista por correo electrónico, Kersffeld dijo que alrededor de 20 de las personas que describió tienen una importancia significativa para el desarrollo económico, científico, artístico y cultural de Ecuador. En plena forma. Entre ellos se encuentra el refugiado austriaco Paul Engel, quien se convirtió en un pionero de la endocrinología en su nueva patria. , manteniendo una carrera literaria separada bajo un seudónimo Diego Viga; Trude Sojka, superviviente del campo de concentración, que soportó la pérdida de casi toda su familia y se convirtió en una artista de éxito en Ecuador; y tres judíos italianos (Alberto di Capua, Carlos Alberto Ottolenghi y Aldo Muggia) que fundaron una empresa farmacéutica que sentó precedentes, Laboratorios Industriales Farmacéuticos Ecuatorianos, o LIFE.

Marcado por el Amazonas y los Andes, Ecuador no podría haber parecido un destino menos probable. Eso cambió después del pogromo de la Kristallnacht en Alemania y Austria en 1938, las Leyes Raciales en Italia el mismo año, la ocupación de gran parte de Checoslovaquia en 1939 y la caída de Francia en 1940. Ecuador se convirtió en “uno de los últimos países americanos en mantener abiertas sus fronteras”. la posibilidad de inmigración en sus distintos consulados en Europa”, escribe Kersffeld. “Una de las últimas alternativas cuando todos los demás puertos de entrada a las naciones americanas ya estaban cerrados”.

El cónsul en Estocolmo, Manuel Antonio Muñoz Borrero, expidió 200 pasaportes a judíos y fue admitido póstumamente en 2011 como el primer Justo entre las Naciones de su país en Yad Vashem. Otro cónsul, José I. Burbano Rosales en Bremen, salvó a 40 familias judías entre 1937 y 1940. Pero Muñoz Borrero y Burbano fueron relevados de sus deberes después de que el gobierno ecuatoriano supo que estaban ayudando a judíos. Burbano fue trasladado a Estados Unidos, mientras que Muñoz Borrero permaneció en Suecia y extraoficialmente continuó sus esfuerzos. Recientemente, el gobierno ecuatoriano honró a Muñoz Borrero cuando restableció al difunto diplomático como miembro de su cuerpo.

_________________________________________________________________________

Daniel Kersffeld habla en una ceremonia del gobierno ecuatoriano en honor al difunto cónsul Manuel Antonio Muñoz Borrero el 9 de noviembre de 2018. Durante el Holocausto, Borrero rescató judíos a través de su puesto de cónsul en Suecia, pero el gobierno ecuatoriano lo despojó de su puesto. La ceremonia del 9 de noviembre lo reintegró como miembro del servicio exterior ecuatoriano./Daniel Kersffeld speaks at an Ecuadorian government ceremony honoring the late consul Manuel Antonio Munoz Borrero on November 9, 2018. During the Holocaust, Borrero rescued Jews through his position of consul in Sweden, but the Ecuadorian government stripped him of his position. The November 9 ceremony reinstated him as a member of the Ecuadorian foreign service. (Courtesy Daniel Kersffeld)

_______________________________________________________________

Inmigrantes judíos en el barco hacia Ecuador./Jewish immigrants on the boat to Ecuador. (Eva Zelig)

________________________________

“Creo que la mayoría [de los judíos] que fueron a Ecuador lo vieron como un trampolín”, dijo. “Nadie sabía dónde estaba en los mapas”. Pero, dijo, “siento una enorme gratitud. (Eva Zelig“/”I think most [Jews] who went to Ecuador saw it as a stepping-stone,” she said. “Nobody knew where it was on maps.”But, she said, “I feel tremendous gratitude. (Eva Zelig)

_________________________________

Ecuador as a Shelter for Jews

While many countries did less than their all when Jews sought refuge from the Holocaust, the tiny South American nation of Ecuador made an outsized impact. Named for the equator, the former Spanish colony became an unlikely haven for an estimated 3,200-4,000 Jews from 1933 to 1945. Few of these refugees knew Spanish upon arrival, and many could not quite locate their new home on the map. Yet some emigres achieved success in diverse fields, from science to medicine to the arts, helping Ecuador modernize along the way. The growing menace of Hitler and Mussolini spurred Jewish immigration to Ecuador, supported by the small local Jewish community. President Jose Maria Velasco Ibarra promoted the country as a destination for German Jewish scientists and technicians suddenly unemployed due to Nazi anti-Semitism. Ecuador-based academic and author Daniel Kersffeld published a book in Spanish about this little-known story, “La migracion judia en Ecuador: Ciencia, cultura y exilio 1933-1945.” “Jewish Immigration in Ecuador: Science, Culture and Exile 1933-1945.” The author surveyed 100 biographical accounts in writing the book. In an email interview, Kersffeld said that around 20 of the individuals he profiled hold significant importance for Ecuador’s economic, scientific, artistic, and cultural development.They include Austrian refugee Paul Engel, who became a pioneer of endocrinology in his new homeland, while maintaining a separate literary career under a pseudonym; concentration camp survivor Trude Sojka, who endured the loss of nearly all of her family and became a successful artist in Ecuador; and three Italian Jews — Alberto di Capua, Carlos Alberto Ottolenghi and Aldo Muggia — who founded a precedent-setting pharmaceutical company, Laboratorios Industriales Farmaceuticos Ecuatorianos, or LIFE.

Kersffeld learned that LIFE’s co-founders had been expelled from Italy in 1938 after the passage of dictator Benito Mussolini’s anti-Semitic Racial Laws. He found they represented a wider story in Ecuador from 1933 to 1945 — “a larger number of Jewish immigrants who were scientists, artists, intellectuals or who were in distinct ways linked to the high culture of Europe.”

Marked by the Amazon and the Andes, Ecuador could not have seemed a less likely destination. That changed after the Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany and Austria in 1938, the Racial Laws in Italy the same year, the occupation of much of Czechoslovakia in 1939 and the Fall of France in 1940. Ecuador became “one of the last American countries to keep open the possibility of immigration in its various consulates in Europe,” Kersffeld writes. “One of the last alternatives when all the other ports of entry to American nations were already closed.”

The consul in Stockholm, Manuel Antonio Munoz Borrero, issued 200 passports to Jews and was posthumously inducted in 2011 as his country’s first Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem. Another consul, Jose I. Burbano Rosales in Bremen, saved 40 Jewish families from 1937 to 1940.But Munoz Borrero and Burbano were both relieved from their duties after the Ecuadorian government learned they were helping Jews. Burbano was transferred to the US, while Munoz Borrero stayed in Sweden and unofficially continued his efforts. Recently, the Ecuadorian government honored Munoz Borrero when it restored the late diplomat as a member of its fore.

Ecuador’s Jewish-exile community in the 1940s at the Equatorial monument in Quito, Ecuador

Emigrantes a Ecuador al campo/Jewish immigrantes to Ecuador in the countryside

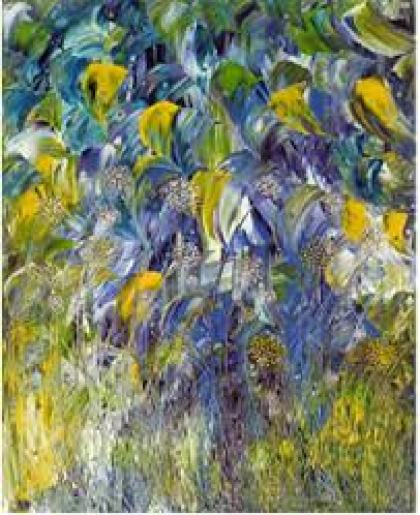

Artista judío-checo-ecuatoriana Trude Sojke/Czech-Ecuadoran Jewish Artist Trude Sojke

Arte de Trude Sojka

Emigrante judío A Horvath que trajo la tecnología del transmisor radial a las selvas amazonas, cuando ayudaba a Shell Oil a buscar el petroleo durante los 1940s/ Jewish immigrant Al Horvath brought radio transmitter technology to the Amazon jungle in Ecuador while helping Shell Oil look for petroleum there in the 1940s. (Courtesy / Daniel Kersffeld)

_____________________________________

Adaptado de The Times of Israel/Adapted from the The Times of Israel